https://omgadam.netlify.app/road-to-hell-game.html. Lots of bugs and errors in the game and the second patch are about 195 Mb big!

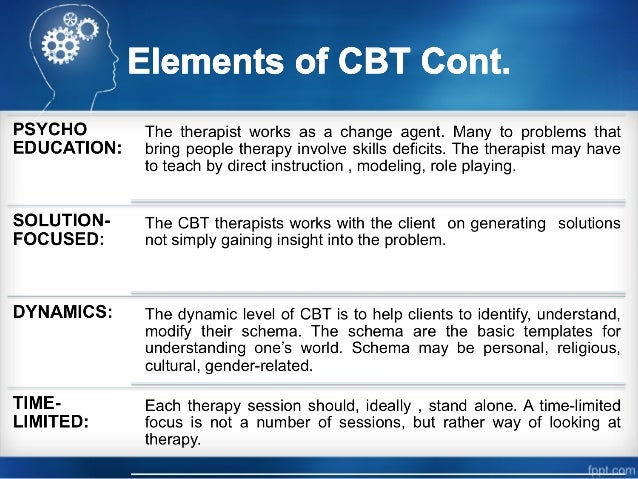

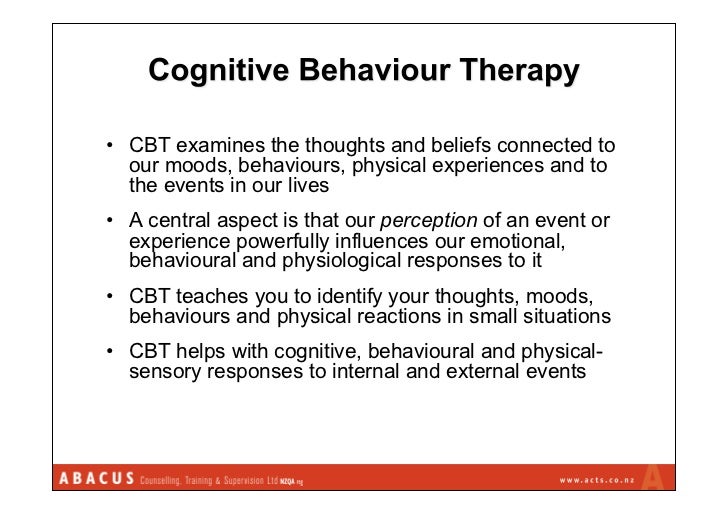

We used cognitive behavioral therapy methods, as well as relapse prevention techniques, so that, at the end of the 6-month therapy, Paul was able to quit this addiction and lead a normal life with. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Cognitive behavioral therapy is widely used today in addiction treatment. CBT teaches those recovering from addiction and mental illness to find connections between their thoughts, feelings and actions, and increase awareness of how these things impact recovery. The cognitive behavioral therapy techniques help in solving many problems that occur from maladaptive thoughts and behavioral patterns. Therapists and patients (clients) make use of the above-mentioned techniques to cure most of the psychological problems in a time-bound and effective manner.

Gambling activities are present in almost every culture (). Although most individuals who gamble do not develop gambling-related problems, 1–3% of the adult population and even higher proportions of adolescents develop pathological gambling. This disorder is characterized by a progressive and maladaptive pattern of gambling behavior that leads to loss of significant relationships, job, educational or career opportunities and even commission of illegal acts. Societal costs of pathological gambling are estimated at over 5 billion dollars annually (2). Individuals who meet some, but not full, criteria for pathological gambling are often considered problem gamblers (2–), a condition that affects an additional 1.3% to 3.6% of the population and is also associated with substantial individual suffering and societal burden. Few pathological gamblers seek treatment, although about half appear to recover on their own (,). Gamblers Anonymous (GA) is the most popular intervention for pathological gamblers, but less than 10% of attendees become actively involved in the fellowship, and overall abstinence rates are low (2). Several medications have shown promise in the treatment of PG, but to date there are no FDA-approved medications for this disorder. Cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT) has shown efficacy in the treatment of pathological gambling ().

As with all psychiatric disorders, cultural factors such as the beliefs and values of one’s group, its normative patterns of help-seeking behaviors and, in the case of immigrants, the process of acculturation, often play an important role in the initiation and maintenance of problem and pathological gambling (). Furthermore, culture can powerfully influence the phenomenology of the disorder and the type of treatment acceptable for the patients (,). We present the case of a woman with pathological gambling whose beliefs, deeply rooted in her culture, contributed to the perpetuation of her disorder. A description of how these beliefs were also manifest in the patient’s family further illustrates the role of culture in the patient’s behavior. The case also serves to exemplify the use of CBT for pathological gambling and how the assessment of the patient’s beliefs helped tailor the intervention to make it culturally consonant while still eliciting behavioral change.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Pathological Gambling

We present a case of a patient with pathological gambling based on a cognitive-behavioral relapse prevention skills manual (,) that has shown efficacy in a large randomized trial (). It consisted of 10 weekly 60-minute psychotherapy sessions. The primary treatment goal was gambling abstinence.

CBT is intended to help stop gambling behavior by helping the patient acquire specific skills using exercises introduced in each therapy session. Semi-structured homework assignments are used to facilitate practice and reinforcement of the skills learned during the week’s session. Treatment provides an overall framework to facilitate lifestyle changes and restructure the environment to increase reinforcement from non-gambling behaviors.

During therapy, therapist and patients track gambling and non-gambling days, and patients are strongly encouraged to reward themselves for non-gambling days (,). Patients are taught to break down their gambling episodes into their precipitants (triggers), the thoughts and feelings that ensue, and the evaluation of both positive and negative consequences of their behavior. This process, called functional analysis, is one of the components of CBT. It is typically learned in the early stages of treatment and used throughout it, as needed. It consists of an analysis of the chain of thoughts, feelings and actions that lead the individual to place a bet, as well as an analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of gambling versus non-gambling. The purpose of functional analysis is to help patients realize that although the short-term consequences of gambling are pleasant (having fun or the possibility of winning some money), the long-term consequences are often very severe and include not only financial problems, but also difficulties with the family, friends, work or the law. Functional analysis helps the patient understand their gambling activities from a behavioral perspective and identify steps that can be taken to stop the process at different points, so that they can effectively reduce the probability of gambling in the future in response to similar situations ().

Patients are also taught to brainstorm for new ways of managing both expected and unexpected triggers and to handle cravings and urges to gamble. Throughout the treatment patients are provided with tools and skills, such as engaging in alternative pleasant activities or calling a friend when experiencing cravings, to abstain from gambling. These skills help patients cope with triggers both internal (e.g., boredom, irrational beliefs) and external (e.g., turning down an offer to gamble, not entering gambling venues).

Each session concludes with a weekly tracking form to record triggers, cravings, or interpersonal difficulties and response strategies for those situations. Therapy also includes one session dedicated to addressing irrational thoughts. In the final session, the patient is encouraged to discuss possible events over the next ten years and consider how these events may affect future decisions to or not to gamble.

Case Presentation

Ms. A was a 51-year-old Haitian woman who immigrated to the United States with her family when she was 25 years old. She married soon after her arrival, settled in a large city in the East Coast, and had two daughters. At the time of treatment, Ms. A had been working as a secretary for a business office for over 20 years.

Ms. A started gambling in Haiti at an early age, occasionally betting small amounts of money on domino games and local lotteries. Initially, her gambling behavior did not have any immediate adverse consequences although, paralleling the effects of early substance use, it may have predisposed her for pathological gambling in adulthood (). At the age of 30, five years after her arrival in the United States, Ms. A began to gamble periodically in hopes of improving her financial situation. Over the next ten years, she began to lose increasing amounts of money playing slot machines at casinos. By age 40, Ms. A would often spend the entire weekend sitting at the slot machines without sleeping, and eating only snacks. After a few years of intense gambling activity, she was able to stop on her own without treatment. However, at age 45, she relapsed, a common experience among pathological gamblers (), into playing lottery tickets.

The relapse occurred after having very vivid dreams that she interpreted as depicting number combinations she should play in the lottery. Growing up in Haiti, she had learned to look for symbols in her dreams since, in her culture, dreams were believed to convey important life messages often represented by numbers. As a teenager in her country, books about dreams and numbers were very popular, and she read them fervently. She would also frequently gather with her family members to discuss her dreams and their meanings, and agree on the numbers the dreams suggested should be played on the lottery. These conversations about dreams and numbers among her family members continued to be an important topic in their almost daily conversations after immigrating to the US.

As the duration of her relapse lengthened, Ms. A gambled greater amounts of money and more frequently. She became increasingly preoccupied with thoughts about gambling and number combinations. Her continuous efforts to reduce or stop gambling resulted in irritability and restlessness. Although she was aware that she was losing more money than she was winning, she would often gamble the day after losing money in hopes of winning back (“chasing”) her losses. She concealed the extent of her gambling and her financial situation from her family. Occasionally, she had suicidal ideation, but never made any suicide attempts, which are common among pathological gamblers ().

As a result of her gambling behavior, Ms. A. began to experience financial problems. One of Ms. A’s primary motivations to seek treatment was the constant arguments with her husband about the monetary constraints caused by her gambling activities. She also felt ashamed and guilty about the money spent gambling over the years. Although she experienced financial difficulties due to the gambling behavior, Ms. A did not commit any illegal acts to finance her gambling activities, nor did she rely on others to bail her out of financial difficulties.

Ms. A reported that her gambling did not interfere with her work and household chores because it only took her a few minutes during the day to purchase tickets at convenience stores located close to her workplace and home. She never missed days at work and performed her work well. She only noted mild difficulties concentrating at work during the minutes prior to the lottery deadline. She did, however, note the impact of gambling on her social activities. She reported being more socially withdrawn, spending less time with her daughters, and increasing conflict with family members due to her overall irritability.

Although comorbidity is common among pathological gamblers (–), Ms. A did not meet full criteria for any other psychiatric disorder. She did, however, report experiencing several depressive symptoms over the past few weeks, including little interest or pleasure in doing things, feeling guilty, and becoming easily annoyed or irritable. Thus, the patient met the following DSM-IV criteria for pathological gambling: 1) increased preoccupation with gambling; 2) having the need to gamble increasing amounts of money to achieve excitement; 3) unsuccessful efforts to stop gambling; 4) restlessness and irritability when trying to stop gambling, 5) after losing money gambling, returning another day in order to get even (“chasing” her losses); 6) hiding the extent of her gambling from her family; and, 7) feeling she was jeopardizing her relationship with her husband as a result of her gambling. Although Ms. A did not report: 1) gambling as a way to escape from problems or in order to relieve a dysphoric mood; 2) commiting any illegal acts to finance her gambling; or, 3) relying on others to provide money to relieve her financial situation, overall Ms. A manifested a persistent and recurrent maladaptive gambling behavior that met 7 of 10 DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for pathological gambling (five or more are needed for a diagnosis of pathological gambling), and was not accounted for by a manic episode.

Treatment

Since the initial treatment contact, Ms. A clearly stated her main goals were to abstain from gambling and improve her financial situation and her relationship problems. One of her main concerns was that although she had been able to abstain from gambling in the past, she found herself unable to do so after her last relapse. At the initial evaluation, Ms. A scored 20 on the Yale Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale adapted for Pathological Gambling (PG-YBOCS), a valid and reliable measure of pathological gambling severity (with range 0–40).

Early in treatment, Ms. A soon identified her dreams and visions as her main triggers for gambling. She described two types of dreams. In one type of dream, either Ms. A actually “saw” numbers, or one or more characters in the dream disclosed “winning” numbers. These dreams were very vivid and constituted very strong triggers to gamble. The other type of dream, to which she referred as visions, was more common and happened throughout the day. Those dreams contained images and actions of different individuals she knew, including family members, friends, coworkers, and neighbors. For these visions, Ms. A had predetermined number conventions derived from Haitian culture and conversations with her family. That is, the images and actions she saw conveyed number combinations. As an example, she would describe a dream in which she saw an unknown little girl talking to her uncle. Ms. A said that dreaming about children meant the number 32, while dreaming about a male family member represented the number five, leading her to create different sets of numbers with these three digits. In other dreams, the numbers were more obvious, such as in a dream in which she saw herself walking on a street and seeing a license plate with a certain number. Ms. A typically woke up everyday and started attributing numbers to the images that appeared in her dreams and visions. She would write down the numbers and generate a list of different combinations to buy a series of lottery tickets that day. Depending on the results of the first drawings, she would generate a new series of combinations for the next drawing. Ms. A. also reported other triggers for gambling (15), including her wish to solve her financial problems, her family’s constant involvement in gambling activities, and the sight of gambling advertisements or convenience stores that sold lottery tickets.

Having identified a variety of triggers, Ms. A. began to address them to minimize the possibility that they would results in gambling. For example, she started making the conscious effort to avoid recalling her dreams. This was difficult due to her longstanding habit of recalling them, but was effective in controlling her gambling behavior. She also stopped carrying with her the list of numbers generated in the morning, and later replaced generating the list with doing her weekly therapy homework assignments. During treatment, therapist and patient maintained a tracking graph on a grid of gambling and non-gambling days. Graphing all gambling and non-gambling days together onto a sheet, the patient was able to visualize her progress. After the third session, the patient was able to notice that she had decreased the amount of money spent on gambling and bought lottery tickets every other day rather than daily.

The patient also started to actively avoid some other gambling triggers. She avoided the convenience store close to work, and stopped watching gambling T.V. shows and advertisements, including the lottery results. She contacted the customer service at the casinos she used to visit, requesting that they stop sending her their invitations and publicity. She purposely kept busy during the hour prior to the lottery deadline, to avoid buying lottery tickets for the next drawing.

For Ms. A, the most effective strategy to abstain from gambling was to conduct functional analyses every time she experienced urges to gamble. Describing her gambling activities, the patient talked about the anxiety she experienced before buying lottery tickets and the frustration, shame, and guilt she felt once the results were published and she was confronted by the amount of money lost that day. Conducting functional analyses allowed the patient to see how, despite a few wins, the overall result was always monetary loss and greater debt. The patient gradually started to feel less excited about thoughts of winning. Eventually, even winning became an anxiety-provoking situation.

The patient experienced intense frustration on one particular occasion when she had a dream about the winning number, but did not feel the dream with enough strength. She hedged her bets, rather than put all her money on the winning number. This experience filled her with doubt on her abilities. She started to experience her ability to foresee the future in visions and dreams as an unpleasant responsibility. In the past, stressful familial events had also appeared in her dreams before they happened, but she had been unable to influence those events, a very painful experience. She realized now that, similarly, “knowing” the correct number did not lead her to win. As a result, her gambling activities were making her financial situation worse. At that time, around the midpoint of the treatment, the patient’s PG-YBOCS scores had decreased to 11. Tracking the number of gambling days revealed the patient was now gambling once or twice a week.

The therapist conceptualized the knowledge acquired through her dreams as a special type of erroneous belief. Erroneous beliefs are commonly found in gamblers and often manifest as beliefs in “lucky days” and “lucky streaks”. They can also include ignorance of the true probabilities of winning and failure to understand the independence of events (“I lost three times on this slot machine, so I should win soon”).

In CBT, at least an entire session is generally devoted to understanding and challenging erroneous beliefs. The purpose is to help the patient identify their thinking errors regarding their odds of winning. However, in this case, given the strong family and cultural support for the patient’s cognitions, the therapist’s approach was to subtly question Ms. A’s beliefs, without confronting them directly. The therapist focused on having the patient recognize that the dreams and visions did not consistently provide her with winning numbers, rather than challenging the irrationality of the belief. This approach, and the patient’s progressive perception of her dreams and visions as a burden, strengthened the patient’s decision to ignore her dreams and visions related to gambling. In so doing, a main trigger of her gambling was removed.

During subsequent sessions, the therapist coached Ms. A on assertiveness and gambling refusal skills. It was difficult for the patient to control her urges to buy lottery tickets after participating in “number conversations” with her family members or coworkers. She decided during one of these sessions to tell her mother and sisters about her wish to abstain from gambling. However, after two weeks of abstinence, Ms. A lapsed one day. She bought a lottery ticket after one of her sisters told her a very vivid dream that she believed to be the winning number for the next drawing. Using the gambling tracking chart, the patient was able to see that weekends, when she spent longer hours with her family members, represented a risk.

This lapse led Ms. A to identify family members and conversations about numbers as additional triggers to gamble. Ms. A had to reiterate to her family members to avoid discussing numbers, dreams, or visions when she was present. This was difficult initially, as her family would pressure her to continue gambling, given its importance in family life and beliefs. However, Ms. A eventually prevailed and found it helpful to avoid these conversations. Having the strength to voice her opinions and wishes also raised her self-esteem and self-efficacy. Around that time, she learned that one of her brothers had a gambling problem when they were living in Haiti. This knowledge increased her motivation to remain abstinent, as she remembered the financial struggle her brother experienced before immigrating to the United States.

The last two sessions served to solidify Ms. A’s gains and refine her skills. The patient had already achieved abstinence and felt strong and confident. Her urges were mild. The patient spent more time in alternative pleasant activities, such as physical exercise, going out with friends or to church, helping organize holiday festivities, and participating in other community activities. She also spent more time with her husband and daughters during the weekdays and attended social gatherings with them.

Although Ms. A. had initially reported that her gambling activities never affected her work, toward the end of treatment, she noticed an improvement in her ability to concentrate and complete tasks more efficiently. Her abstinence helped improve her relationship with her husband, with whom she now argued less. She was also excited about being able to buy more things for her home as a result of not spending money on gambling. At the end of the tenth session the patient’s PG-YBOCS gambling scores had decreased to 2, within the normal range. The gambling tracking chart now was an upright line, since she had not gambled for a month on a row. The process of tracking non-gambling days increased Ms. A’s perception of control of her gambling behavior, and she reported it became a strong motivation to remain abstinent.

After completing the 10 weekly sessions, Ms. A continued to come to therapy for monthly follow-up sessions. At follow-up, 10 months later, Ms. A continued to abstain from gambling. During these sessions, the therapist and patient continued working on strengthening the skills learned during the acute treatment and brainstorming alternatives to gambling. The patient was also referred to a therapy group for women who want to remain abstinent from gambling, which Ms. A found helpful. It is likely that Ms. A will require continuous treatment and follow-up for pathological gambling. If the patient’s preferences or situation change, other therapeutic alternatives, such as medication for other psychiatric symptoms, motivational interviewing, or Gamblers’ Anonymous, could also be considered.

Case Discussion

Pathological gambling is a common disorder with severe consequences for patients and their families. At present, the treatment with best empirical support is CBT. This case describes its general principles, and provides an example of how CBT techniques can be adapted depending on the characteristics of each patient. In particular, the case of Ms. A illustrates the contribution of beliefs, especially those part of a cultural system, to the perpetuation of a patient’s disorder; the influence of family members’ attitudes, moved by their cultural beliefs and values, in shaping behavior; and the consideration of these issues to guide specific interventions, such as challenging irrational thoughts or helping patients devise strategies to change their behavior in a culturally-congruent manner.

Log into Facebook to start sharing and connecting with your friends, family, and people you know. My online vegas casino.

Irrational beliefs are important factors in the initiation and maintenance of many psychiatric disorders, including pathological gambling. Identifying them, pointing out their consequences, and progressively challenging them are key aspects of CBT. For example, special dates, playing numbers encountered during the day, or lucky days, create in some patients a sense of possessing a special knowledge that putatively increases their chances of winning. Those beliefs can be powerful triggers to gamble even after long periods of abstinence, and often trigger a relapse. It is not uncommon to find pathological gamblers who act on the numbers they see in their dreams. For Ms. A, however, dream and numbers interpretation were particularly important because they had been part of her belief system since her childhood, long before she developed a gambling problem. Furthermore, in her case, the belief that dreams foretold the numbers to play on a given day was supported by her family and her culture.

For these reasons, it was anticipated that engaging Ms. A in viewing this belief as irrational would be difficult. Subtly and progressively questioning her beliefs, as was done in this case, was an adjustment of a CBT technique to the patient’s culture, since standard treatment usually challenges cognitive distortions more directly. Challenging her belief directly would have probably appeared to be minimizing the patient’s and her family’s cultural norms. This could have led the patient to argue for the “truth” of symbolism in dreams, make her refuse to use CBT techniques and possibly cause her to leave treatment prematurely, feeling misunderstood or misjudged. Because the patient had come to treatment due to her gambling losses, it was believed that focusing instead on the less central belief of the ability of dreams to provide winning numbers would be much more effective with her.

By doing so, the patient was able to distance herself from her gambling behavior, as she started to perceive throughout treatment that her number system was unreliable. For example, as the therapist explored the triggering effect of dreams, she asked the patient about her experience with the dreams, their accuracy at predicting winning numbers, and her feelings about her failure to win despite playing the numbers suggested by the dreams. These questions helped create discrepancy between the patient’s beliefs (and wishes) and reality. Building the challenge to these beliefs, the therapist was able to engage the patient in treatment and help her begin avoiding external and internal triggers.

Knowledge about the role of these beliefs in the lives of the patient and her family was also crucial in this case. Following a period of abstinence, the patient suffered a lapse to gambling when her sister urged her to play certain numbers that she had interpreted from a dream. Contrary to relapses, where the patient returns to the addictive behavior for an extended period of time, brief lapses such as what occurred with this patient can be very useful to the treatment of addictive disorders. Although much of the relapse prevention treatment approach focuses on helping the patient build skills to avoid relapse, lapses can help the therapist and the patient identify situations for which the patient needs more help. These lapses can be best used therapeutically if they occur while the patient is still in treatment, because then the patient and therapist can quickly analyze the lapse and incorporate the lessons learned into the treatment. The lapse that occurred during Ms. A’s treatment helped her to identify her family discussions about dreams and numbers as triggers to gamble, and allowed the therapist and the patient to explore ways of dealing with them.

The lapse was also instrumental in helping the patient set limits with her family in conversations on gambling, numbers, and dreams. Solely pursuing an approach focused on setting limits could conflict with her cultural norms of family interactions, which valued harmony among family members, and fail to elicit from her family’s support. Given the familial endorsement of these beliefs about dreams and numbers, however, finding an acceptable way of setting limits was a key aspect of achieving and maintaining abstinence from gambling. Rather than readily teaching the patient feedback and assertiveness approaches often used in mainstream American culture, eliciting from Ms. A how limits could be set within her family and culture made it easier for her discuss her difficulties with her family and enlist their support in not having those conversations in her presence (had this approach not worked, Ms A and the therapist would have considered alternative strategies and developed additional skills to be more assertive if necessary).

Ms. A’s approach also exemplifies the broader aspects of how family or other support systems can be helpful in stopping gambling. Although the family was a trigger to gambling, it also provided an important image for Ms. A that strengthened her resolve to remain abstinent from gambling-- her brother’s experience. This fact was particularly important given that several studies suggested that pathological gambling may have a familial component. Consistent with those studies, associations have been reported between pathological gamblers and allele variants of polymorphisms at dopamine receptor genes, the serotonin transporter gene, and the monoamine-oxidase A gene (–). Twin studies have also suggested a genetic component in the etiology of problem and pathological gambling ().

Conclusion

We have presented the case of a Haitian woman that illustrated the role of culture in the phenomenology and treatment of pathological gambling. The case showed how cultural beliefs can contribute to the etiology of psychiatric disorders, how the manifestation of symptoms can vary by culture, and how CBT can be integrated within belief systems of different cultures.

Cultural perceptions related to psychiatric disorders may also influence treatment-seeking behaviors. For cultures with highly permissive beliefs towards gambling, it might be difficult to label certain gambling behaviors as a psychiatric disorder, which could consequently reduce the likelihood that individuals in need will seek services.

The advantages of learning about the patient’s culture to provide appropriate and efficacious treatment have been well established (). Those benefits include the ability to build trust, to demonstrate openness and interest by recognizing cultural belief systems and the role they play in the initiation and maintenance of a patient’s condition, and to adapt the treatment to use those beliefs as help rather than barriers to treatment.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by NIH grants DA019606, DA020783, DA023200 and MH076051 (Dr. Blanco), MH60417 and DA022739 (Dr. Petry), the New York State Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services (Dr. Blanco) and the New York State Psychiatric Institute (Drs. Oquendo and Blanco).

Footnotes

Disclosures All authors declare no competing interests.

References

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Techniques Kids

Abstract

Several types of psychotherapy are currently used to treat pathological gamblers. These include Gambler's Anonymous, cognitive behavioral therapy, behavioral therapy, psychodynamic therapy, and family therapy. Research into which types of psychotherapy are the most effective for pathological gambling is limited but is a growing area of study. Group therapy, namely Gambler's Anonymous, provides peer support and structure. Cognitive behavior therapy aims to identify and correct cognitive distortions about gambling. Psychodynamic psychotherapy can help recovering gamblers address core conflicts and hidden psychological meanings of gambling. Family therapy is helpful by providing support and education and eliminating enabling behaviors. To date, no single type of psychotherapy has emerged as the most effective form of treatment. As in other addictive disorders, treatment retention of pathological gamblers is highly variable. Understanding the types of psychotherapy that are available for pathological gamblers, as well their underlying principles, will assist clinicians in managing this complex behavioral disorder.

Introduction

Pathological gambling is a complex biopsychosocial disorder that can have dramatic and devastating consequences on individuals and families. Given the expansion of legalized gambling and society's current acceptance of gambling, the development of effective treatments (pharmacological and nonpharmacological) to stem the development of pathological gambling is crucial. At the present time, a number of different treatment modalities have been applied to pathological gamblers, but no standardized practice guidelines have been developed. In the clinical setting, pathological gamblers are offered a variety of treatment options, including pharmacotherapy, individual psychotherapy, group therapy, and family therapy. Of these, the most likely treatment modality to be used is psychotherapy. Several types of psychotherapy have been employed with pathological gamblers and range from psychoanalysis, cognitive behavioral therapy, psychodynamic psychotherapy, behavioral therapy, family therapy, and group support.

The principles of psychotherapy for pathological gamblers tend to share those used in substance abuse treatment settings; this is due to shared themes of loss of control, preoccupation, and continued engagement in the behavior despite negative consequences. Despite there being a wide variety of psychotherapies practiced with pathological gamblers, the current evidence demonstrating their effectiveness has only recently been the subject of more intense study. Clinical experience suggests that these psychotherapies work by improving motivation to change and self control; precisely how these changes take place and what specific factors are responsible have been the subject of ongoing investigation.

Comprehensive treatment for pathological gambling involves more than psychotherapy, most notably the emerging use of medications to contain the symptoms of this disorder. For those interested in the psychopharmacological management of pathological gamblers, there are a number of well-written reviews by Grant and Hollander.2,

This article is the last of a three-part series focusing on pathological gambling. Part 1 described the biopsychosocial consequences of gambling, and Part 2 focused on portraying the vulnerable faces of pathological gambling. This part will describe the currently available psychotherapeutic strategies that are used with pathological gamblers. Particular emphasis will be placed on illustrating psychotherapy principles that are unique to treating pathological gamblers. Psychotherapeutic treatments for pathological gambling are likely to be used with more frequency and by more providers as additional funding becomes available for pathological gambling treatment and as more gamblers present to treatment. Therefore, it is essential that the clinician be familiar with the various types of psychotherapies that have been formally examined in pathological gamblers.

Throughout history, a number of different approaches have been utilized to deal with pathological gamblers. Some have been dramatic, including eviction from the community to cutting off of the hands, while others have been more supportive, such as individual and group psychotherapy. The primary aim of psychotherapy for pathological gamblers is to achieve total abstinence from gambling. More specifically and more realistically, psychotherapies aim to improve self control, identify ways to deal with risky situations, provide an outlet to address guilt/shame, and teach ways to deal with gambling urges and cravings. Treatment outcomes for pathological gamblers demonstrate that pathological gamblers respond to treatment and that many demonstrate benefits even if they are in treatment for short periods of time.4 Although there are numerous forms of psychotherapy that have been applied to pathological gambling, only a few have been subjected to rigorous study, and the following will be reviewed here: Gambler's Anonymous, cognitive behavioral therapy, the behavioral therapies, psychodynamic psychotherapy, and family therapy.

Gambler's Anonymous

The most available form of psychotherapeutic treatment is Gambler's Anonymous (GA). Formed from the model of Alcoholics Anonymous, GA is widely available in most states and internationally; there are over 1,000 GA chapters in the United States. GA was created in 1957 in Los Angeles, and the meetings follow the 12-step self-help model. The twelve steps are identical to those utilized for substance abuse, except that gambling replaces alcohol or drugs. Meetings are either open or closed and can be found through Internet and phone directories; they are free to members and are available seven days a week in many urban cities. The treatment philosophy of GA is similar to that of other addictive self-help groups—in order to recover, one must “work the steps,” which include gaining a sponsor, completing the 12 steps outside of the meetings, and gaining emotional support and strength by a peer support group. GA members are not allowed to bail members out and are not allowed to take monetary donations. Directives of GA include: 1) attend as many meetings as possible; 2) don't gamble for anything (even office pools); 3) take life “one day at a time;” and 4) utilize the members of the meeting for support. Gambler's Anonymous has a sister organization, Gam-Anon, which is modeled after Ala-Anon and is a support group for family and friends of pathological gamblers. Often, meetings are held at the same time and place as GA meetings and these groups provide a much needed source of emotional support, problem solving ideas, and understanding of pathological gambling.

Although GA is probably the most referred to form of treatment for pathological gamblers, it only has a small amount of empirical data supporting its efficacy. Stewart prospectively followed 232 members of Gambler's Anonymous and found that eight percent of GA members remained totally abstinent after one year and that seven percent remained totally abstinent at two years. This finding has not been replicated and deserves further attention.

In another study, Taber found that 74 percent of clients in a gambling treatment program who were sober went to at least three GA meetings a week, suggesting that GA participation might predict better outcomes. Effectiveness for Gam-Anon has also not been definitely shown. Johnson compared spouses who went to GA versus spouses who did not go to GA and did not find any differences in total time of abstinence from gambling.

One of the reasons why abstinent rates may be so low is that many gamblers do not stay with GA. Much more research is needed to understand the factors for why certain gamblers remain in GA and others do not. Gamblers that have comorbid attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and high expression of impulsivity (verbally and behaviorally) may have difficulty in engaging and retaining information from GA. Secondly, understanding how abstinent members use GA, in particular what is meant by “working the steps,” would be an important contribution.

Another important characteristic of GA is that all gamblers are considered to have the same disease—there is little distinction between machine gamblers and non-machine gamblers or between male and female gamblers. As a result, clinicians are urged to be aware of what the demographics are of the GA meeting to which they refer patients. Knowing this may be especially important in retaining patients. Finally, clinicians need to be aware that there are clinical differences between gamblers who remain in GA versus those who do not go. Gamblers who attend GA tend to be older, have more severe gambling problems, and more interpersonal tension at home. Most significantly, those who have a past history of attending GA are more likely to remain engaged in professional, individual therapy, suggesting that GA may promote treatment retention. Overall, despite the lack of definitive evidence, the widespread availability and accessibility of GA make it a viable therapeutic option.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

The basic principle of cognitive behavioral therapy for pathological gambling is to identify negative thoughts, cognitive distortions, and erroneous perceptions about gambling that are responsible for continued gambling. CBT has been shown to be effective in a number of other psychiatric and addictive disorders., Based on this experience, clinicians and researchers turned toward CBT for pathological gambling in the hopes of achieving the same degree of effectiveness.

Cognitive behavioral therapy for pathological gamblers can occur in a variety of methods ranging from individual to group therapy. CBT may employ a range of techniques from didactic to role-playing to challenging beliefs and attitudes. In most outpatient settings, CBT for pathological gamblers usually lasts for 8 to 15 sessions. The therapy is very active and often includes assignment of homework, feedback, and direction from the therapist.

In etiological theories of pathological gambling, the presence of cognitive distortions about gambling often fuel continued gambling. For instance, Ladoceur showed that erroneous thoughts about gambling persist regardless of what type of game is being played. Commonly, gamblers might believe that they are “due to win” or “I won't lose while I am wearing my lucky shirt.” The “gambler's fallacy” is the persistent belief that a win will be coming soon even though outcome of bets are based on random chance. Pathological gamblers also believe their gambling abilities are unique in that they are able to control random events. Pathological gamblers also feel that gambling is the solution to life's problems, especially financially. Finally, gamblers often have distorted views of the odds of a game or how the casino industry contributes to gambling addiction. Once these erroneous perceptions are identified, clients are directed to alternative ways of thinking, which, in theory, will lead to reduced gambling or improved control over gambling.

The cognitive component of CBT deals with identifying cognitive distortions, erroneous perceptions, and false expectations of gambling. A common exercise is to describe risky life situations that might trigger relapse. This might include driving by a local casino, having extra cash on hand, or recently being paid. Once identified, the therapist and the client devise a problem-solving approach on how to avoid or handle that situation. CBT for gamblers appears to work best for highly motivated and insightful gamblers. It is not recommended for those who are struggling with insight, have extensive comorbid disorders, or who have trouble sustaining attention. One of the strength's of CBT is that it can identify an individual's unique erroneous thoughts or cognitive distortions (i.e., not all gamblers have the same cognitive distortion), and this type of therapy provides the flexibility to identify each of them separately.

Behavioral management techniques to use with pathological gamblers include limiting access to money and/or increasing the degree of difficulty to gamble. For example, Internet gamblers are encouraged to disconnect the Internet while casino gamblers may be eligible to sign up for a self-exclusion ban from the casino. Ongoing data regarding the effectiveness of self-exclusion on lifetime gambling rates is ongoing, but early evidence suggests this type of intervention may be helpful for motivated gamblers with strong social supports., Recovering gamblers are also encouraged to take themselves off mailing lists from the casino, to meet with a financial planner, to cancel all credit cards, and to turn over control of money to another person. Each of these behavioral interventions is designed to increase the difficulty of obtaining access to money to gamble. Much like the philosophy of limiting access to drugs of abuse, there has been very little data to empirically support these behaviors even though they may appear to be quite sensical on the surface.

In terms of data to support CBT for gamblers, there have been several studies documenting its effectiveness. Ladouceur has demonstrated that CBT is quite effective for early intervention of pathological gamblers. In this study, 66 gamblers were assigned to either CBT or to a wait-list control condition. Those who received CBT had significantly improved outcomes in perception of control, frequency of gambling, perceived self-efficacy, and desire to gamble. Sylvain reported similar results of CBT effectiveness versus waiting-list controls in 29 male pathological gamblers. Most recently, Petry evaluated the efficacy of a manualized CBT delivered by counselors versus CBT that is self-administered.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Techniques Te…

Future research will emphasize whether lessons learned during cognitive behavioral therapy last or whether they fade with time. Furthermore, client matching of CBT and the appropriate gamblers is a future need of development. Pathological gamblers who may not be indicated for CBT included those with psychotic disorders, active suicidal ideation, or ongoing substance abuse, which may lead to intoxicated states. Nevertheless, CBT appears to be a promising psychotherapeutic treatment for pathological gamblers and should be employed wherever possible.

Behavioral Therapies

These types of therapy for pathological gambling are based on the principles of classical conditioning or operant theory. One of the reinforcing properties of pathological gambling is the intermediate reinforcement schedule. Treatment methods that attempt to change this behavior include aversion therapy, imaginal desensitization, and in-vivo exposure with response prevention. Theoretically, behavior is reshaped by changing learned responses and by reducing arousal or other rewarding sensations experienced from gambling. Behavioral therapies for pathological gambling received significant attention during the late 1960s and 70s but are not as widely available as other forms of psychotherapy for pathological gambling.

Aversion therapy consists of reducing the frequency of a behavior by associating gambling with an unpleasant stimuli, such as an electrical shock. Two case reports describe the use of electric shock in reducing gambling behavior., Larger studies were never performed and aversion therapy fell out of popularity as other, less ethically challenging, types of therapies emerged.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Techniques Ptsd

McConaghy and Blasczynski have published several case reports and case series on the use of imaginal desensitization and imaginal relaxation as a therapy to reduce pathological gambling. This is a variant of systematic desensitization and is designed to deal with the hyperactivation of the arousal state-caused gambling-related cues. Essentially, the therapist guides the gambler through an imagined gambling session, evoking physical and emotional responses. The therapist then employs breathing and relaxation techniques to create an alternative response to gambling by reducing aroused states to a manageable level.

Echebura23 used individual stimulus control and exposure with response prevention in 69 male slot machine gamblers. This form of therapy was found to result in an 83-percent total abstinence rate 12 months after completion of the therapy. This type of therapy is designed to deal with the cravings and urges for gambling by increasing confidence in the ability to impose self control over gambling. Despite the high response rate, this particular form of therapy has not been replicated in other types of pathological gamblers or within the US.

Psychodynamic Psychotherapy

During the early 20th century, psychoanalysts viewed pathological gambling as an unconscious drive to punish oneself, often in order to diminish themes of self hatred and hostility toward authority figures. Several psychoanalysts have applied fundamental techniques to pathological gamblers, primarily during the 1950s and 60s. There have been very few efforts to document the effectiveness of psychoanalysis; one case series by Bergler reports having treated 60 pathological gamblers with a total abstinence rate of 75 percent.25 Unfortunately, he does not provide specifics on the types of gamblers treated and what specific techniques of psychoanalysis were used. Psychoanalysis is thought to be helpful to pathological gamblers by resolving interpersonal conflicts within therapy, and presumably a reduction in gambling behavior would follow.

Individual psychotherapy for pathological gamblers depends on the skill, knowledge, and experience of the psychotherapist. Psychodynamic psychotherapy for pathological gamblers focuses on identifying the meaning behind ongoing gambling and resolving conflicts that may have led to it. Furthermore, psychodynamic therapy focuses on reducing the guilt and shame associated with the consequences of pathological gambling. Pathological gamblers, like other addictive disorders, often employ immature defense mechanisms, such as denial, acting out, rationalization, minimization, and rejection. Under stress, many of these defense mechanisms emerge. Individual psychotherapy focuses on identifying these mechanisms and developing healthier defense mechanisms.

To date, there is very little data to demonstrate the efficacy of psychodynamic psychotherapy in pathological gamblers. No recommendation of how many sessions of psychodynamic therapy has been established, nor has there been a systematic overview of the elements of therapy that confer success. Rosenthal and Rugle described a psychodynamic approach to treating pathological gamblers that includes reducing denial, addressing defense mechanisms, stopping the chasing cycle, clarifying motivations to gamble, and increasing the motivation of the client.

Based on clinical experience, the effectiveness of psychodynamic therapy is probably due to a number of factors, including having a venue to discuss guilt/shame, reflection, nonjudgement, and psychoeducation. As with GA, many gamblers come in and out of individual therapy. Many struggle with honesty, ambivalence, motivation, or a combination of all three. To assist patients in selecting resources, there are national and state certification programs for individual therapists in the treatment of pathological gambling, but the type of therapy offered is usually not made known until asked.

Family Therapy

One of the main areas of negative consequences of pathological gambling is the direct effects pathological gambling has on family functioning. Pathological gambling can lead to divorce, internal strife, domestic violence, and can reinforce enabling behaviors which perpetuate continued gambling. Family therapy with pathological gamblers focuses on identifying problematic family dynamics and seeks to lessen chaos and conflict. A secondary purpose of family therapy for pathological gamblers is to corroborate the pathological gamblers' report or denial of gambling behavior. Typically, methods used in family therapy of pathological gamblers may range from cognitive-behavioral to focusing on understanding reasons to gamble. To date, few studies have examined the impact of family therapy on individual gambling behaviors but research initiatives are ongoing. One study by Tepperman demonstrated improved marital functioning after brief marital therapy.27 Lee reported that eight couples improved on measures of well being and life satisfaction immediately after a short, systems-based couples therapy. Family therapy may be underused in pathological gamblers, namely because of lack of training, availability of therapy, and clinical evidence to support its use. Involving the family in treatment is essential in order to fully understand and address the consequences of continued gambling behavior.

Harm Reduction

Taken directly from the philosophy employed in drug abuse treatment, some therapists may attempt to apply these theories to pathological gambling. These would be interventions geared at controlling or limiting one's gambling. The premise is that if some pathological gamblers are driven by cognitive distortions and an unawareness of the possible consequences of ongoing gambling, then interventions in this area may be enough to restore control over gambling losses. At first glance, harm reduction may appear to also be indicated for pathological gamblers who are in the early stages of their disorder. Examples of harm reduction techniques include setting time limits to gambling, playing with cash instead of credit (less likely to gamble more with cash), and playing with predetermined loss limits. One study has investigated using controlled gambling as a treatment outcome; in this study, Blaszczynski, et al., followed 63 pathological gamblers after they had completed a behavioral treatment program. Social functioning and subjective distress were found to be equal between those who had achieved total abstinence and those who were considered controlled gambling.

Table 1

Available Psychotherapy Resources for Pathological Gamblers

| Gambler's Anonymous www.gamblersanonymous.org Phone: 213.386.8789 |

| Gam-Anon www.gam-anon.org |

| National Council on Problem Gambling www.ncpgambling.org |

| National Gambling Helpline Phone:800.522.4700 |

The spirit of harm reduction has a certain appeal for pathological gamblers—many gamblers are impulsive and have high expectations for themselves, so that any ongoing struggles to achieve total sobriety may be interpreted as yet another failure. Pathological gambling, though, carries some unique clinical features that complicate the utility of the harm reduction model. Gambling is not self-limiting; that is, it can continue forever provided there is enough money. More importantly, it is debatable whether a reduction in gambling frequency or wagering is an improvement at all. Gambling's unpredictability means that some gamblers may actually win. Furthermore, every time a patient gambles, there is always the risk of incurring significant damage in a very short amount of time. Pathological gambling is about consequences of gambling, which means that a lifetime of consequences can arise after one single session of gambling.

Helplines

Although not a formal mechanism of therapy, gambling helplines exist in 35 states. These helplines are operational 24 hours a day and are answered by trained mental health professionals. Helplines provide information about pathological gambling, referrals to GA, and to gambling certified providers, and can also screen callers for gambling problems. They have also been known to manage acute crises, such as suicidality and financial desperation. Pathological gamblers do not easily enter treatment and when compelled to seek treatment, an immediate response may be beneficial. The effectiveness of helplines needs to be studied on a formal basis, particularly in understanding its impact on changing gambling behaviors.

Other Issues to Consider in Psychotherapy of Pathological Gamblers

Cognitive Behavioral Techniques For Anxiety

Comparisons to substance abuse treatment. Although pathological gambling shares many clinical features with other addictive disorders, there are notable differences that need to be noted during the course of psychotherapy. Techniques that work for substance abuse may not work for pathological gambling. For instance, gambling cannot be detected by an objective test; thus, attendance and participation in meetings/ therapy does not necessarily mean abstinence. Another difference is that pathological gamblers may actually win money while engaging in their behavior. Few drug addicts report coming home with money. How does a therapist deal with these consequences when the gambler's behavior has resulted in profit? Lastly, pathological gamblers cannot blame their irrational behaviors on the intoxicating effects of drugs or alcohol. As a result, there is a stark realization that any destructive behavior that occurred is a direct result of themselves and not a result of intoxication. In turn, this often leads to intense feelings of guilt, shame, and embarrassment, which if not explored will undoubtedly lead to more gambling.

Addressing finances. By definition, pathological gamblers have altered views on money and what money represents to them. Any form of psychotherapy with pathological gamblers requires a discussion about money. A great number of pathological gamblers continue to gamble simply because debts are so large that they do not see any other way of recovering their money other than through gambling. Pathological gamblers who are seeking treatment are encouraged to turn their finances over to someone else. Most therapists do not receive any training on financial planning, bankruptcy laws, or loan repayments. As a result, therapists who intend to work with pathological gamblers must educate themselves about how to properly manage money, otherwise a significant contributing factor to pathological gambling will go unaddressed.

Future Directions

There are several emerging psychotherapies that are being examined for efficacy in pathological gamblers. Contingency management, a therapeutic strategy that has been shown to be effective for substance use disorders, particularly opiate and cocaine abuse, has not been extensively evaluated for pathological gamblers. Potential applications of this would include providing rewards to gamblers for not gambling or for completing portions of a treatment program. Contingency management operates using positive reinforcement and looks to identify ways to reward healthy behaviors instead of punishing ongoing addictive behavior.

Virtual counseling (Internet or computerized therapy) is another treatment option. Presently there are only a few gambling specialty treatment programs, and one way to expand treatment services is to provide telephone and Internet counseling. Some pathological gamblers may be reluctant to enter individual or group therapy due to stigma, lack of resource availability, or denial. Numerous chat rooms have emerged for GA 12-step fellowship and are available anonymously 24 hours a day.

Conclusions

There are several types of psychotherapy treatments available for pathological gambling. Most accessible is Gambler's Anonymous and Gam-Anon. Cognitive behavioral therapy and individual therapy (usually psychodynamic psychotherapy) are also frequently employed by gambling treatment providers. Compared to other psychiatric disorders, the amount of evidence supporting the effectiveness of these treatments is not nearly as extensive, but it is a growing field. Given that there are no FDA-approved pharmacotherapies for pathological gambling and that knowledge of the biological basis of pathological gambling is just recently emerging, this demonstrates how important it is to develop psychosocial treatments. The most effective psychosocial treatments appear to be a combination of treatment approaches, including GA along with individual and cognitive behavioral therapy. Research is also showing that treatment and early intervention works and that those with pathological gambling no longer have to rely solely on the passage of time to improve.